As the Second World War was coming to an end, anti-Stalinists on the Left found themselves facing a difficult problem. The Soviet Union had won a resounding victory against Nazi Germany. Stalin was widely perceived, especially in left and liberal circles, as an ally. Many expected the Soviet Union to open up a bit, to introduce some elements of democracy.

Communist Parties in many countries — including the USA — had grown enormously, and in some Western countries, including Italy and France, seemed to be on the cusp of power. The Rand School Press in New York City, linked to the American Socialist Party (which was then in deep decline), rushed to get this book into print to help thwart the Communists.

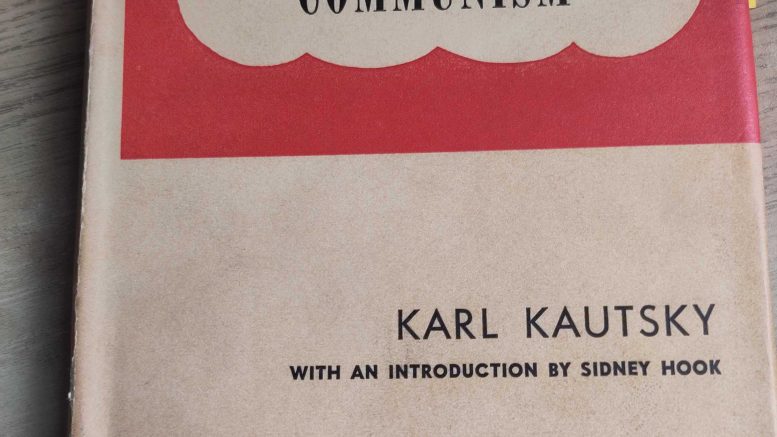

The eminent philosopher Sidney Hook wrote a long introduction. David Shub (author of a later excellent biography of Lenin) and Joseph Shaplen translated and edited the book. But it’s a very strange book — a collection of writings of Kautsky’s from his last years (1932-37), though none of the chapters cite sources. We don’t know when each chapter was written, what has been left out, or where the articles originally appeared. An attempt has been made to make this read like a coherent book, starting with essays on the origins of socialism and running right up to the rise of Nazism.

Kautsky was the original anti-Stalinist, having written critical letters and articles about the Bolshevik regime just days after Lenin’s seizure of power in 1917. He died in 1938. By 1945, his ideas about Communism had begun to take hold in Social Democratic and Labour parties; by 1952, with the re-foundation of the Socialist International in Frankfurt, its founding declaration was lifted almost word for word from Kautsky’s writings on the Soviet Union.

It is clear that much was not understood about what was happening in the Soviet Union at the time Kautsky wrote some of these essays. He noted the purges and show trials, but seemed to believe that they reflected growing unrest in the USSR, which was not the case. Similarly, he acknowledges the terror famines of the early 1930s which at least in the case of Ukraine were a form of genocide. He seems unaware of their full scale.

Kautsky’s didactic style, very much in the mode of German academia, was already dated by the 1930s. While books like Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia remain vivid indictments of Stalinism and are well-read today, Kautsky is largely forgotten. This collection, for example, has not been reprinted and can only be found in some libraries and used bookstores.

Nevertheless, it remains a useful book. The most surprising part was Kautsky’s use of what would now be called “alternate history” — a few pages of “what if” scenarios had the Bolsheviks decided in early 1918 to accept the results of the elections to the Constituent Assembly and form a coalition government with the Social Revolutionaries and Mensheviks. Knowing what actually happened makes this painful reading.