This is the talk I gave on Thursday, 14 September 2017 at Prospero’s Bookshop in Tbilisi.

I want to start by thanking Peter Nasmyth and Prospero’s Books for hosting us this evening.

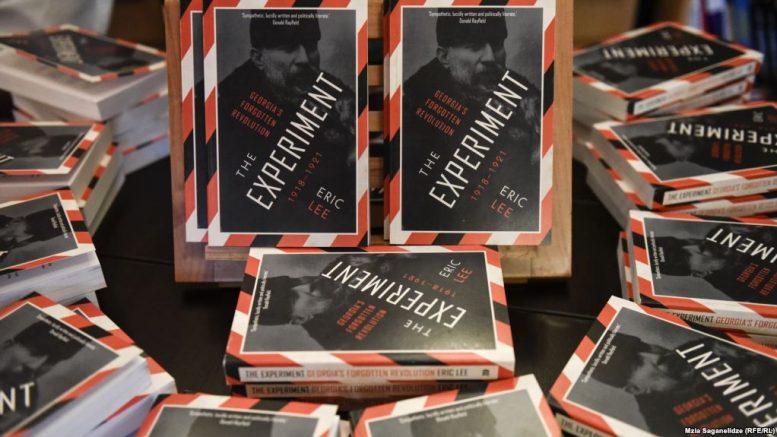

I also want to welcome all of you – thank you for coming. Thank you in particular to friends and family who have come from California and New York, from the UK, France, Switzerland, Israel and elsewhere, for being here with us to celebrate the publication of this book.

I want to especially acknowledge the presence of Dan Gallin, former general secretary of the International Union of Foodworkers. Dan encouraged me to write this book back in the 1980s. He who reviewed a very early version of it and then more recent ones. His whose ideas and values have been an inspiration to me and many others. Thank you, Dan, for being here with us tonight.

We live in an age of “fake news” – but we also live in an age of “fake history” too.

The history of the first Georgian republic, for example, is a history that was deliberately covered-up, hidden, concealed first of all from the Georgian people themselves, but also from the world.

The villain in this story is of course the Communist Party, which ruled Georgia with an iron fist for nearly seven decades.

If you are too young to remember that regime, consider yourself lucky. But you can have a taste of it by visiting the Stalin museum in Gori, a disgraceful site that is – incredibly – controlled by the Georgian state today. That museum celebrates the life and work of the twentieth century’s greatest mass murderer. It is an example of “fake history.”

The Soviet era was a time when no dissent was permitted, only one opinion was tolerated and lies were told day and night by state-controlled media, by the schools, by political leaders.

Lies were told for seven decades about the first Georgian republic.

That it was a tool of British or German imperialism.

That it was a ruthless dictatorship which suppressed the heroic efforts of the workers and peasants, led by the local Bolsheviks.

That instead of distributing land to the peasants, the regime propped up the nobility.

That when faced with a popular uprising, its leaders fled to western Europe without putting up a fight.

All of these were and are lies. They were told by the Communist Party in order to make certain that people would forget what really took place in Georgia in the years 1918-21.

And it was not only the Stalinist regime in the USSR and in Georgia which lied, and which tried to bury the memory of the first Georgian republic.

It was also Trotsky, the great dissident, the conscience of Bolshevism, who wrote a thoroughly dishonest account of Georgia following the Red Army invasion. Trotsky, though he commanded the Red Army, did not order that invasion. He didn’t even know about it. But due to a twisted sense of loyalty to the Communist Party, Trotsky felt obligated to defend the crushing of independent Georgia.

His book is still in print and still being read. In a recent debate I had with some British Trotskyists, they still quoted from his book. They still accepted his analysis as being valid. And yet Trotsky’s book, like the official Communist publications from the Soviet era, is “fake history.”

What actually, happened in Georgia then, in those three short years of independence, was nothing short of remarkable.

The most important socialist thinker of the time was Karl Kautsky, a leading figure in the German Social Democratic Party, who was known as the “Pope of Marxism.” He visited Georgia in 1920 together with a delegation of European socialist politicians. He stayed for several weeks, and wrote a short book the following year. Kautsky was convinced that the Georgian Democratic Republic was the antithesis of the regime created by Lenin and the Bolsheviks in Russia.

He wrote: “In comparison with the hell which Soviet Russia represents, Georgia appeared as a paradise.”

The Georgian republic was not a paradise, of course not. But it was a functioning democracy, it had free elections and a multi-party system. Trade unions grew rapidly and were independent of the state. They were so strong that they compelled the Constituent Assembly to include the right to strike in the draft constitution. The cooperative movement thrived and there were signs that in some sectors of the economy cooperatives had already replaced privately-owned businesses.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of the Georgian Social Democrats was the land reform. Georgia, like Russia, was a country where the emancipation of the serfs in the 1860s led not to their freedom, but to their impoverishment. In Russia, under the leadership of Lenin and the Bolsheviks, the city and the countryside were in a constant state of war. Armed detachments of urban workers were sent out of Petersburg and other cities to grab as much food as they could from peasants who refused to sell it. Millions of people died unnecessarily in man-made famines.

But not in Georgia. Here, the Social Democrats were not the enemies of the peasants. Here the peasants were a key constituency of that party. Peasant support for the Social Democrats preceded the 1917 revolution by more than a decade. When the Social Democrats came to power, the land reform they enacted was welcomed by the peasants.

There was no war between city and countryside, no famine, no starvation. The later horrors of forced collectivisation under Stalin had no parallel in independent Georgia. The Georgian Social Democrats applied a rigorous Marxist analysis to the question of land and concluded that giving the land to the peasants was the best way to begin building a new society – and they were proven correct.

Kautsky tells the whole story about political democracy in Georgia, about the land reform and about the powerful and independent trade unions and cooperatives that dominated Georgian society.

Unfortunately, his book was soon forgotten as the Soviet presence in Georgia became permanent. The Social Democrats across Europe who condemned the Russian invasion in 1921 eventually lost interest in Georgia. The exiled Georgian leaders like the former president Noe Zhordania, eventually were isolated, ignored and forgotten.

And now a century has passed, and next year we will celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Georgian declaration of independence on May 26th, 1918.

There can be no better time to put an end to “fake history” and to tell the true story of the Georgian experiment.

This is important both for Georgians and for the world.

For the Georgians, telling the truth about the first Georgian republic is essential. Without knowing where you come from, you cannot know where you are going.

For Georgia as a country to become all it can be, to be a more just and equal society, it needs to re-learn, or learn for the first time, the incredible story of the first Georgian republic.

For everyone else, the story of the Georgian Social Democrats and the republic they led for three years is important for this reason: it helps teach us what we are talking about, when we talk about democratic socialism.

I became a democratic socialist many years ago, and I remain one today. And my democratic socialism is the socialism of Karl Kautsky, Rosa Luxemburg, and Julius Martov.

But it is also the socialism of the Georgians – Zhordania, Tsereteli, Ramishvili, Khomeriki, and all the long-forgotten leaders of the Georgian Social Democratic Party.

Zhordania and his comrades took the ideas of Marx, Kautsky, Luxemburg and Martov, and tested them in practice, here in Georgia.

The society they created, while not perfect, was indeed a paradise compared to the hell on earth that the Bolsheviks created in Russia. Kautsky was right about that.

In rediscovering the real history of the first Georgian republic, we honour their memory – and we learn that another revolution was possible, a humane and democratic one.

Thank you.