The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) exists to certify that products coming from the world’s forests are produced responsibly. You may never had heard about the FSC, but if you look around your home, you’ll see its logo everywhere — on your toilet paper, inside your books, maybe even on your furniture.

The Bonn-based global organisation is a network of over 1,200 members in 89 countries. Some of those are corporations, some are non-governmental organisations (e.g., Greenpeace), some are individuals. And some are even trade unions — large, well-known unions. These include UNIFOR in Canada, IG Metall in Germany, the Australian Manufacturing Workers Union as well as others in Brazil, Chile, India, Malaysia and Sweden.

What does the FSC logo on your kitchen towel roll mean? Among other things, it means that forestry workers are treated fairly. And that’s not some general, meaningless platitude. The FSC says clearly that it “shall uphold the principles and rights at work as defined in the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work (1998) based on the eight ILO Core Labour Conventions.”

For those of you who may not be completely up-to-date with that International Labour Organisation declaration or the “core conventions” referred to, here’s a reminder:

- freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining;

- the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour;

- the effective abolition of child labour;

- the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation; and

- a safe and healthy working environment.

There’s more to it than that, but you get the general idea.

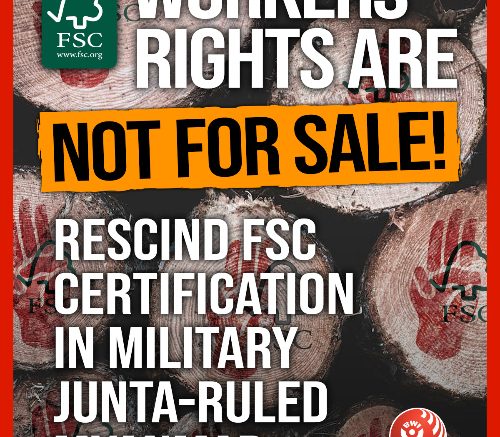

The FSC will obviously not allow forestry products made in countries like Myanmar to be certified, right? After all, the military regime in that country has arrested over 26,000 dissidents and killed around 400 trade unionists. It has one of the worst human rights records in the world. And it is currently at war with its own people.

Incredibly, the FSC continues to certify products from Myanmar as being “responsibly” sourced and compatible, somehow, with that ILO declaration and related conventions.

When pushed by unions to explain this, the FSC said it was waiting for the publication of an ILO Commission of Inquiry report. That report was published on 4 October 2023, three months ago, but still the FSC continues to certify Myanmar’s forestry products. They now claim to be waiting for a “final version” of that report before considering what to do about Myanmar.

The ILO report is remarkably clear about what is going on in Myanmar. And it’s worth noting that such ILO “Commissions of Inquiry” are a rare event to begin with. In the more than 100 years that the ILO has existed, there have only been 14 of them. As the report notes, “Such Commissions represent the highest level of ILO supervisory mechanisms.”

The ILO report “concluded that the actions taken by the military authorities since February 2021 have resulted in far-reaching restrictions on the exercise of basic civil liberties and trade union rights, as well as in the incapacity of trade unionists to engage in trade union activities.”

The Commission made a number of immediate recommendations, including calling on the military rulers of Myanmar “to immediately cease all forms of violence, torture and other inhumane treatment against trade union leaders and members; to release and withdraw all criminal charges against trade unionists detained in relation to the exercise of their civil liberties and legitimate trade union activities; and to fully restore the protection of basic civil liberties suspended since the coup d’état. The recommendations also urge the military authorities to end the exaction of all forms of forced or compulsory labour by the army and its associated forces, as well as forced recruitment into the army.”

There’s not a lot of room for interpretation there: the military junta ruling Myanmar is clearly beyond the pale. And yet the Forest Stewardship Council is still not sure, still waiting for further evidence.

Or maybe it’s just that the fees companies pay the FSC to get that logo on their products are not something the organisation is keen to lose.

Building and Wood Workers’ International (BWI), the global union federation for forestry workers, has tried to persuade the FSC to reconsider. BWI represents 12 million workers worldwide. But the FSC isn’t listening. For that reason, BWI has launched a major online campaign on LabourStart calling on the FSC to “to promptly revoke and terminate its certification system and Chain of Custody certificates in Myanmar.”

It’s important that the campaign receive the widest possible circulation. The FSC has to hear the loud and clear voice of people everywhere demanding that they immediately stop certifying Myanmar’s forestry products.

But questions also have to be asked of the unions that are FSC members. Surely they oppose the FSC decision to continue certifying forestry products from Myanmar? Some of those unions are even BWI affiliates. The labour movement must come up with a clear position expressing its unanimous support for the people of Myanmar and against the military regime. It’s not enough to issue statements condemning violations of human rights in the country. If the FSC doesn’t change course, those unions should at the very least terminate their membership in the organisation.

The people of Myanmar, including those working in its forests, deserve nothing less. This is what solidarity means.

This article appears in the weekly newspaper Solidarity.