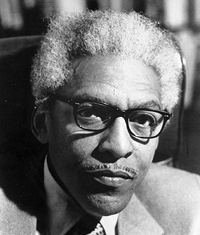

This March marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of Bayard Rustin, the American civil rights leader who passed away in 1987. Rustin is remembered as the organiser of the great 1963 March on Washington at which Martin Luther King gave his “I have a dream” speech.

But to socialists, Rustin’s legacy is richer than that.

I first met Rustin some 40 years ago when he agreed to co-chair the Socialist Party together with Michael Harrington and a long-forgotten Jewish trade union leader named Charles Zimmerman.

Rustin was at that time already unfashionable on the left because of his strong opposition to Stalinism and his unflinching support for the state of Israel.

I was to learn later on in life that being unfashionable was nothing new for Bayard. He was never fashionable, and always championed the causes he believed in, regardless of how unpopular it might make him.

He began his political career with a brief membership in the Communist movement, though he quickly resigned in the wake of the Hitler-Stalin pact. But his being an “ex-Communist” was to haunt him later in life, when Southern racists in the US Congress were to accuse of him of every sin they could think of.

Not only was Rustin a red, they would say, but he was a draft-dodger and a homosexual.

Rustin’s response was to say that he did indeed refuse to serve in the second world war due to his pacifist convictions — and he paid the price for that.

As for his sexual orientation — and this was back in 1963, long before the Stonewall uprising — he denied nothing. He told his accusers to raise that issue, if they dared, with his employers. Later in life, Rustin became an outspoken advocate of gay rights.

Today Rustin’s sexuality, his early flirtation with Stalinism and his pacifism make him to a certain degree acceptable to some parts of the left.

But in his lifetime, his views on the Cold War and on Israel won him few friends on the left.

Rustin moved in the same circles as Max Shachtman, and eventually shared Shachtman’s views on issues like the Vietnam War. While many on the left supported a Communist victory in Vietnam, seeing Ho Chi Minh as some kind of Vietnamese George Washington, Rustin took a more nuanced view, and supported a negotiated settlement that might result in an American withdrawal from the country without necessarily giving Ho control of the south.

When the North Vietnamese army triumphed in 1975, Rustin spoke out at small, hastily-organized demonstrations called to highlight the plight of the “boat people”.

Rustin, like his mentor, the legendary A. Philip Randolph, was a lifelong supporter of the trade union movement. He set up the A. Philip Randolph Institute which for decades served as the centre for Black trade unionists and build strong ties between the Black community and trade unions. And he did this despite the overt racism of many of those unions — a racism he fought against from within the movement, and not as an outsider.

Like most Black leaders in the US in the early 1960s, Rustin felt very close to the Jewish community and the state of Israel. The bonds formed in the early days of the civil rights movement between Blacks and Jews were still quite strong.

When this became unfashionable following Israel’s victory in the 1967 Six Day War and a bitter teachers’ strike in New York City, Rustin remained firm in his beliefs. As tensions increased between the Black and Jewish communities, Rustin organized the Black Americans Support Israel Committee (BASIC) and continued to push for reconciliation between the two communities.

He was by no means uncritical of the Israeli government. On his visits to Israel he pushed hard for better and fairer treatment for the small community of “Black Hebrews” who had settled in the country’s south.

I met Bayard on a number of occasions but the most memorable, to me, took place in 1974. I was then a student at Cornell University, which had established a dormitory for Black students at the same time as many college fraternities were still “whites only”. Our small socialist student organisation campaigned against this renewed form of segregation, pitting us against the campus left which tended to support Black separatism as if it was somehow progressive.

Bayard organised a public message signed by himself and other key Black leaders supporting us, as we were standing in the great tradition of the fight against Jim Crow. And then he agreed to fly up to Cornell and give a public speech on the subject.

We were very concerned about security as emotions were running high, and naively asked Bayard over dinner what he wanted us to do — should we involve the campus police? Absolutely not, he said. The police are never welcome at our meetings.

Bayard spoke to a packed hall full of young Black students with a handful of white socialists in the back. I won’t say that he won them over — that would have been impossible, even for someone with Bayard’s considerable rhetorical skills.

But he did challenge them, and raised the question of — as he put it — “tribalism”.

It was not fashionable to oppose Black separatism back then, in the early 1970s.

But Bayard Rustin never gave a damn about being fashionable.