To the surprise of Russia and everyone, the Ukraine war has taken a remarkable turn in the last few weeks. Initially, the Ukrainians did well by just surviving. Then, they began a slow, systematic counter-offensive in the southern part of the country. Everyone expected that to drag on for a long time. Russia deployed units from its much-depleted army to counter the Ukrainians — thereby creating vulnerabilities in other parts of the front. The Ukrainians speedily exploited these and seized thousands of square kilometres of previously-occupied territory.

Putin’s response has been one of panic. Hastily-called referenda took place in Russian-occupied regions where up to 99% of voters — with guns held to their heads — chose to join the Russian Federation. A botched mobilisation, ostensibly of reservists who already have combat training, has resulted in physical attacks on military recruitment centres across the country and pitched battles between draftees and police in some regions.

Meanwhile, tens of thousands of young Russians have fled the country, some grabbing flights out at exorbitant prices, others driving to the borders with Finland, Georgia, Kazakhstan and Mongolia. The long queues of cars at the Georgian border show how unpopular the war has suddenly become.

All this reminds me of something we saw before in Russia more than a century ago.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, leading thinkers in the Second International were focused on Russia. Karl Kautsky and Alexander Helphand (Parvus) concluded that the autocratic regime was in a precarious position. The tsar, they believed, could be toppled if Russia were to be defeated in a war.

The tsarist regime was foolishly confident that it could easily defeat Japan, which they considered to be a backward country. The Japanese victory in the war, which began in February 1904, provided an opportunity to test Kautsky and Helphand’s hypothesis. It turned out that they were right. In early 1905, a revolution broke out across the empire.

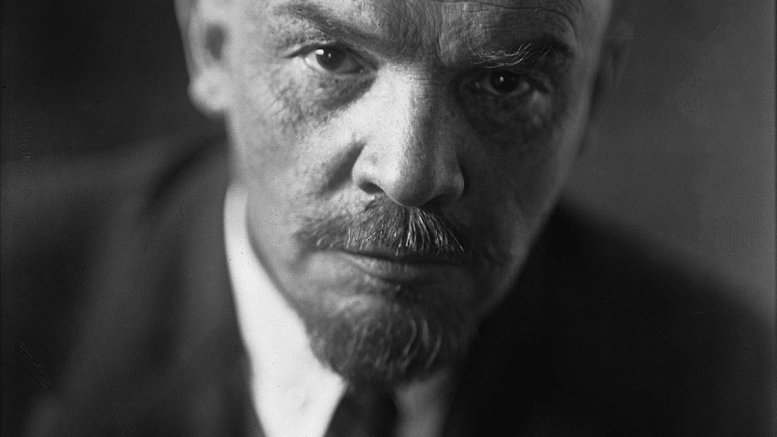

As Lenin wrote after the fall of Port Arthur to the Japanese, “the Russian autocracy, not the Russian people, started this colonial war … The autocratic regime, not the Russian people, has suffered ignoble defeat. The Russian people have gained from the defeat of the autocracy.”

Lenin’s words ring true today as one village after another, one city after another, are liberated by the victorious Ukrainian armed forces. The Ukrainians living in those towns and villages are regaining their freedom. But the Russian people are gaining something too. They are being liberated from the role of colonial occupier — a role they did not seek.

Russia is not a democracy. The last time Russians had a chance to vote in a truly free election in which all parties could participate was in 1917. The governments that have ruled ever since do so without a genuine popular mandate.

When trying to judge the responsibility of the Russian people for the war in Ukraine, that must be remembered. We must also not forget that state censorship has never really gone away in Russia. The population is informed primarily by state-controlled media, such as broadcast television.

This is Putin’s war and his defeat. Until he ordered the mobilisation of his army last week, most young Russians seemed not to care. Thousands were arrested protesting the war, but most were indifferent. Not anymore.

Putin’s army is losing the war in Ukraine. The Ukrainians are winning. And when they win, the Russian people win too.

This is my weekly column for Solidarity.