A little more than a century ago, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin and his wife Nadezhda Krupskaya left their two-room apartment at Spiegelgasse 14 in Zurich, never to return.

They travelled to Russia through Germany at the height of the First World War in the infamous “sealed train.” That train had been provided for them and several of their comrades with the approval of the German General Staff. The Germans hoped that Lenin would be able to force Russia to leave the war.

Here is how Winston Churchill described it: “Lenin was sent into Russia by the Germans in the same way that you might send a phial containing a culture of typhoid or of cholera to be poured into the water supply of a great city, and it worked with amazing accuracy.”

When the war broke out in 1914, Lenin had been living in Galicia, a part of the Austro-Hungarian empire, and was arrested as a possible Russian agent. Eventually, his anti-tsarist credentials got him released and he made it to Switzerland, initially to Bern. In February 1916, he moved to Zurich, attracted by the city’s libraries, especially the Central Library.

Lenin used his time in Switzerland to build the foundations of a new International, one committed to ending the imperialist war. He attended two small international conferences held in neutral Switzerland (at Zimmerwald and Kienthal) at which socialists from warring countries could meet as comrades.

With the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in March 1917, Lenin made arrangements to return home to Russia — and the rest is history.

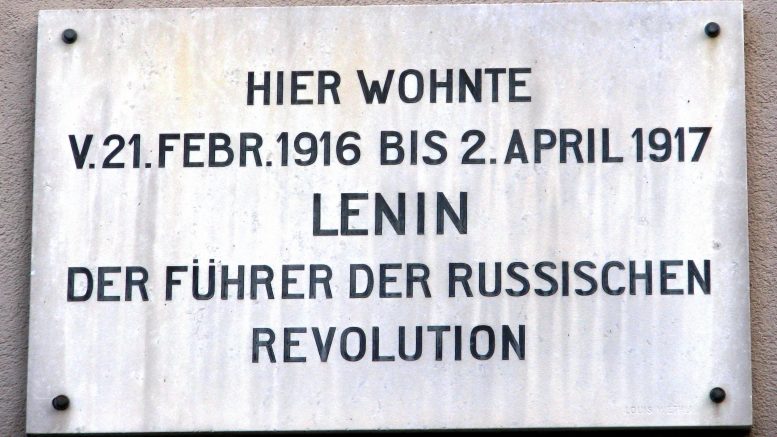

I was in Zurich last week and decided to look for traces of Lenin’s time in Switzerland. I could find none. There is a sign on the building Lenin lived in, but it has been defaced and is no longer readable. I had heard that Lenin’s writing desk, where he wrote two of his more important works, was viewable in the Swiss National Museum.

But as we were told at the museum, there was no such desk in their collection. It turns out that the desk was briefly displayed there in 2017 to mark the 100th anniversary of the Russian revolution. As a museum official wrote at the time, the desk belonged to “the landlord of the two rooms, Titus Kammerer … the furniture belonged to him and remained with him even when the Soviets tried later to buy the furniture off him. They were particularly keen on taking the writing desk to Saint Petersburg, but Jean Kammerer held firm. These days, this piece of furniture is part of the collection belonging to his son, Bruno Kammerer.”

The Swiss National Museum is currently promoting an exhibition about visiting royals, using a photograph of Britain’s Queen Elizabeth on the poster. As for the Russian emigres who flocked to the city in the years before 1917, there is not a word. And as a friendly museum staffer told us, there is also hardly anything at all about the Second World War, as Switzerland “did not participate”.

With Lenin’s desk now apparently in private hands, and no access to his rooms at at Spiegelgasse 14, there is little to remind local people and visitors of a man who was among the most famous to have lived in Zurich. Regardless of what one thinks about Lenin — and socialists have been divided on this issue since the Bolshevik seizure of power in 1917 — no one disagrees with Lenin’s enormous importance.

What a pity that the city that he called home for his final year of exile has not found a way to remember him.

This article appears in the current issue of Solidarity.